Reflections on the Elevation of the Cross

On the occasion of the Feast of the Elevation of the Cross

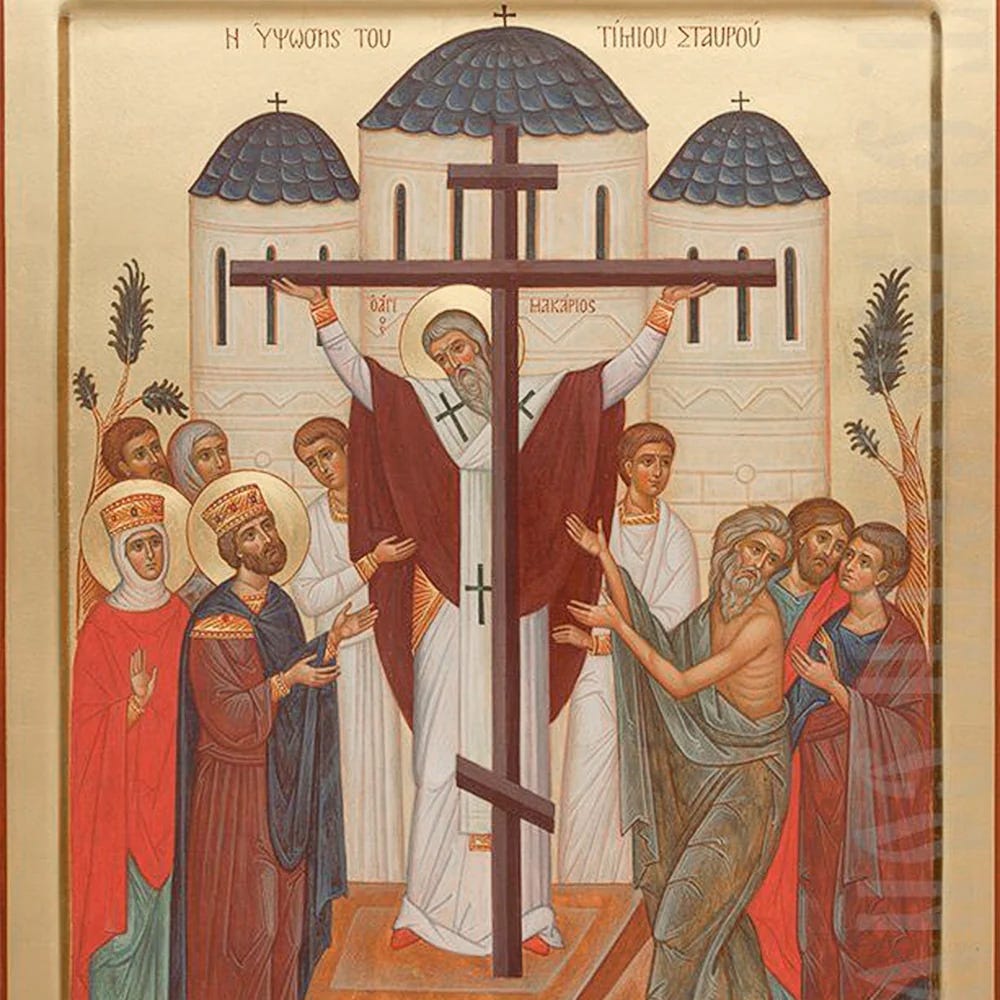

In the Orthodox cathedral where I attend worship a series of twelve icons spans across the altar depicting events celebrated on feast days, starting with Mary’s birth, ending with her dormition. Except the dormition is the eleventh, not the twelfth. The twelfth is a non-biblical event, but one as miraculous as any of the eleven biblical ones: the elevation of the cross.

After Constantine converted the Roman Empire to Christianity in the 300s, he resolve to restore the city of Jerusalem, which had been destroyed by the pagan emperor Hadrian and replaced with a city called Helio-Hadrianopolis devoted to Venus worship. Constantine’s mother Helena was tasked with recovering relics. She went to Helio-Hadrianopolos, began digging, and discovered Christ’s cross buried in the ground at Golgotha. Its veracity was confirmed when they laid it upon a dead man, and the man came to life. The cross was then elevated as the true cross, representing Christianity’s conquest of Rome, the triumph of Christ, 300 years later, on the same spot as his humiliation.

This event marks a significant turning point in the history of Christianity, a liminal point between a period of time that Christianity is, so to speak, about, and a still-ongoing period that looks back to the biblical period. For the next 1500 years Christendom was in some sense the engine of world history, of the actual, profane development of science, industry, technology, communication, trade and so on. The elevation of the cross isn’t in the Bible, it’s in post-Imperial lore, so it doesn’t quite have the same status as earlier events.1

The question arises, did these events really take place? The credo quia absurdus est principle isn’t quite as strong for a non-biblical event as it is for the miracles recounted in the Bible, like, of course, Christ’s own resurrection. Was another man besides Christ really resurrected on Christ’s cross? And now that Christianity is no longer the engine of history, at least not in any avowed form, what are we to make of the event celebrated by this feast? Even if we could say that the secular West is the heir of Christendom, Western culture is distinguished by precisely its dogmatic conviction that miracles are impossible.

For the modern Christian, I propose that the Elevation of the Cross be a reminder that history, ritual, current events and fiction surge forth from a point at which they can no longer be easily distinguished. This point is called reality.

There are plenty of biblical events from after Christ was resurrected and departed the earth, mostly conveyed in the book Acts, which catalogues Pentecost and the evangelical wandering of Paul and others spreading the Christian message.

With enough Laet, the cosmogonical question is rendered moot, at least for me